Installation of R and RStudio, and packages

Basic operations

Some very basic operations you can can carry out in R. Here R works like a calculator:

| addition | |

|

|---|---|---|

| subtraction | |

|

| multiplication | |

|

| division | |

|

| exponential | |

|

| exponential | |

|

Apart from numbers, R can also help us print letters or a string of letters.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Basic objects in R

Creating a variable

When working with large numbers such as 1934929292 and 23992343, we cannot keep them in mind, or for that matter, remember complex computations. So, we have the concept of object or variable.

a <- 1934929292

b <- 23992343

|

|

|

|

Here, we assign <- the first number to “a” and the second to “b”. The <- is called the “assignment operator”. “a” and “b” are called objects or variables. This now enables us to actually use the variables for doing further operations as seen below.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

We can do something similar with strings too.

x <- "language"

y <- "R is my favourite programming language"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Creating a vector

In R, vectors are the most basic data objects. Let us create vectors x and y. We will do that in two ways. One, using the c() function, and the other using the seq() function. ‘c’ combines values into a vector. ‘seq’ is a sequence generator.

x <- c(1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10)

y <- seq(11, 20)

The code above creates two vectors: x and y.

x

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

y

11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20

Adding the two vectors gives:

x + y

12 14 16 18 20 22 24 26 28 30

x * y

11 24 39 56 75 96 119 144 171 200

^ The elements are added element-wise. The operations in R are element-wise.

As an exercise you can try doing the other mathematical operations on the two vectors.

Indexing

The elements in the vectors are indexed. So, to extract an element you need only know its position. To extract the first element in x use:

x[1]

1

This returns 1.

Try the following and see what you get.

y[1:4]

11 12 13 14

y[c(1, 3, 5)]

11 13 15

y[c(-1, -3, -5)]

12 14 16 17 18 19 20

y[-c(1, 3, 5)]

12 14 16 17 18 19 20

Data types

What are the important data types? They can be listed as:

- integer

- numeric

- logical

- character

Let us first create some vectors:

n <- 1 # numeric

i <- 1L # integer

l <- TRUE # logical

c <- "Some string" # character

Here we have four vectors created. x is a numeric vector, y is an integer vector, t is a logical vector, and c is a character vector.

Remember, in R everything is a vector. There are no scalars.

Therefore, all these vectors that we have created are all vectors of length one.

Vector length

To check the length of the vector, use the length() function:

length(n)

1

length(i)

1

length(l)

1

length(c)

1

You can see that all objects created are of length one.

check data class()

Now let us check these vectors using the class() function:

class(x)

"numeric"

class(y)

"integer"

class(l)

"logical"

class(c)

"character"

Now let us create vectors of length > 1:

num_vr <- c(1, 3.0, 5.0) # numeric vector

int_vr <- c(1L, 3L, 5L) # integer vector

log_vr <- c(TRUE, FALSE, TRUE) # logical vector

char_vr <- c("I am", "a", "string.") # character vector

Now get their class.

class(num_vr); length(num_vr)

"numeric" 3

class(int_vr); length(int_vr)

"integer" 3

class(log_vr); length(log_vr)

"logical" 3

class(char_vr); length(char_vr)

"character" 3

Creating a matrix

We learnt to make vectors before, and now we have learnt to understand them a bit more. We now move on to matrices. First, let us create some vectors.

v1 <- 1:5

v2 <- 6:10

v3 <- 11:15

We have three vectors v1, v2, and v3 and we are going to bind them column-wise.

cbind(v1, v2, v3)

v1 v2 v3

[1,] 1 6 11

[2,] 2 7 12

[3,] 3 8 13

[4,] 4 9 14

[5,] 5 10 15

The output just spews out to the console, which is not helpful.

Let us create a variable, my_mat, and store the output:

my_mat <- cbind(v1, v2, v3)

my_mat

Here, we used a function, cbind(), to bind three vectors into three columns.

v1 v2 v3

[1,] 1 6 11

[2,] 2 7 12

[3,] 3 8 13

[4,] 4 9 14

[5,] 5 10 15

Now let us use the class() function on the my_mat variable.

class(my_mat)

"matrix" "array"

The my_matrix is a matrix. It has three columns, v1, v2, and v3. And, as it should be clear now, we used three vectors to create a matrix.

Let us now see an alternate method for creating a matrix.

trial_mat <- matrix(1:20, nrow=5, ncol=4, byrow = TRUE)

trial_mat

[,1] [,2] [,3] [,4]

[1,] 1 2 3 4

[2,] 5 6 7 8

[3,] 9 10 11 12

[4,] 13 14 15 16

[5,] 17 18 19 20

This creates a matrix with 4 rows and 5 columns. The [1,] refers to the first row. The [,1] refers to the first column.

Creating a data.frame

Let us now talk about another kind of data structure, data frame. So, a data frame is similar to a matrix, but it can hold vectors of different classes.

Let us create the same vectors we created previously even though they are still in memory.

num_vr <- c(1, 3.0, 5.0) # numeric vector

int_vr <- c(1L, 3L, 5L) # integer vector

log_vr <- c(TRUE, FALSE, TRUE) # logical vector

char_vr <- c("I am", "a", "string.") # character vector

# Let us use the cbind() function to put them together.

new_mat <- cbind(num_vr, int_vr, log_vr, char_vr)

new_mat

num_vr int_vr log_vr char_vr

[1,] "1" "1" "TRUE" "I am"

[2,] "3" "3" "FALSE" "a"

[3,] "5" "5" "TRUE" "string."

Looking at the output, we know that it is something we do not want.

What is the class of the new variable?

class(new_mat)

"matrix" "array"

The class of the object new_mat is “matrix”.

A matrix can hold data belonging to a particular class.

In this case, every data point is converted into a character. This is called coercion.

Here we need a different kind of data structure that can hold different classes of data. To demostrate this point, let us create some vectors that we will make use of in creating this structure.

# since the numbers are random...

set.seed(1234) # this will make sure we always get the same set of random numbers

plant_height <- rnorm(100, 110, 10)

head(plant_height)

97.92934 112.77429 120.84441 86.54302 114.29125 115.06056

Too many decimals. Let us round it off to two.

plant_height <- round(plant_height, 2)

head(plant_height)

97.93 112.77 120.84 86.54 114.29 115.06

set.seed(237)

flowering_50 <- round(rnorm(100, 100, 10))

head(flowering_50)

102 100 101 100 107 101

set.seed(6438)

spikelet_fertility <- round(rnorm(100, 90, 3), 2)

head(spikelet_fertility)

89.05 89.18 93.49 92.28 88.04 93.61

max(spikelet_fertility)

95.27

set.seed(345)

thousand_seed_weight <- round(rnorm(100, 22, 3), 2)

head(thousand_seed_weight)

19.65 21.16 21.52 21.13 21.80 20.10

Now let us combine the four vectors into a single data structure.

my_data <- cbind(plant_height, flowering_50, spikelet_fertility, thousand_seed_weight)

head(my_data)

plant_height flowering_50 spikelet_fertility thousand_seed_weight

[1,] 97.93 102 89.05 19.65

[2,] 112.77 100 89.18 21.16

[3,] 120.84 101 93.49 21.52

[4,] 86.54 100 92.28 21.13

[5,] 114.29 107 88.04 21.80

[6,] 115.06 101 93.61 20.10

class(my_data)

"matrix" "array"

Let us now create some numbers that we will use as genotype ids. We have 100 observations and that makes it 100 genotypes. We will name the genotypes from “001” to “100”.

Let us use the paste() function to create these ids.

a1 <- paste("00", 1:9, sep = "")

a2 <- paste0("0", 10:99)

genotypes <- c(a1, a2, 100)

genotypes

[1] "001" "002" "003" "004" "005" "006" "007" "008" "009" "010" "011" [12] "012" "013" "014" "015" "016" "017" "018" "019" "020" "021" "022" [23] "023" "024" "025" "026" "027" "028" "029" "030" "031" "032" "033" [34] "034" "035" "036" "037" "038" "039" "040" "041" "042" "043" "044" [45] "045" "046" "047" "048" "049" "050" "051" "052" "053" "054" "055" [56] "056" "057" "058" "059" "060" "061" "062" "063" "064" "065" "066" [67] "067" "068" "069" "070" "071" "072" "073" "074" "075" "076" "077" [78] "078" "079" "080" "081" "082" "083" "084" "085" "086" "087" "088" [89] "089" "090" "091" "092" "093" "094" "095" "096" "097" "098" "099" [100] "100"

Let us add this vector to our my_data object.

newdat <- cbind(genotypes, my_data)

head(newdat)

genotypes plant_height flowering_50 spikelet_fertility

[1,] "001" "97.93" "102" "89.05"

[2,] "002" "112.77" "100" "89.18"

[3,] "003" "120.84" "101" "93.49"

[4,] "004" "86.54" "100" "92.28"

[5,] "005" "114.29" "107" "88.04"

[6,] "006" "115.06" "101" "93.61"

thousand_seed_weight

[1,] "19.65"

[2,] "21.16"

[3,] "21.52"

[4,] "21.13"

[5,] "21.8"

[6,] "20.1"

We have seen this problem before; the entire data getting converted into a character class. To overcome this problem we use the data.frame() function.

field_data <- data.frame(genotypes, my_data)

head(field_data)

genotypes plant_height flowering_50 spikelet_fertility 1 001 97.93 102 89.05 2 002 112.77 100 89.18 3 003 120.84 101 93.49 4 004 86.54 100 92.28 5 005 114.29 107 88.04 6 006 115.06 101 93.61 thousand_seed_weight 1 19.65 2 21.16 3 21.52 4 21.13 5 21.80 6 20.10

This output is more like it. Let us check the class of the df object.

class(field_data)

"data.frame"

It is a dataframe.

A dataframe, unlike a matrix, can hold vectors of different classes.

Using the most important function in R, str(), we get a glimpse of what the field object contains.

str(field_data)

'data.frame': 100 obs. of 5 variables: $ genotypes : chr "001" "002" "003" "004" ... $ plant_height : num 97.9 112.8 120.8 86.5 114.3 ... $ flowering_50 : num 102 100 101 100 107 101 92 95 93 78 ... $ spikelet_fertility : num 89 89.2 93.5 92.3 88 ... $ thousand_seed_weight: num 19.6 21.2 21.5 21.1 21.8 ...

The field object is a data frame with 100 observations and 4 variables. Except for a, which is a factor, plant_height, flowering_50, and spikelet_fertility are numeric. Remember that a is a vector containing the genotype ids. Therefore, a is recognised as a factor here.

Writing data to file

write.csv(field_data, "field_data.csv", quote = F, row.names = F)

Plotting

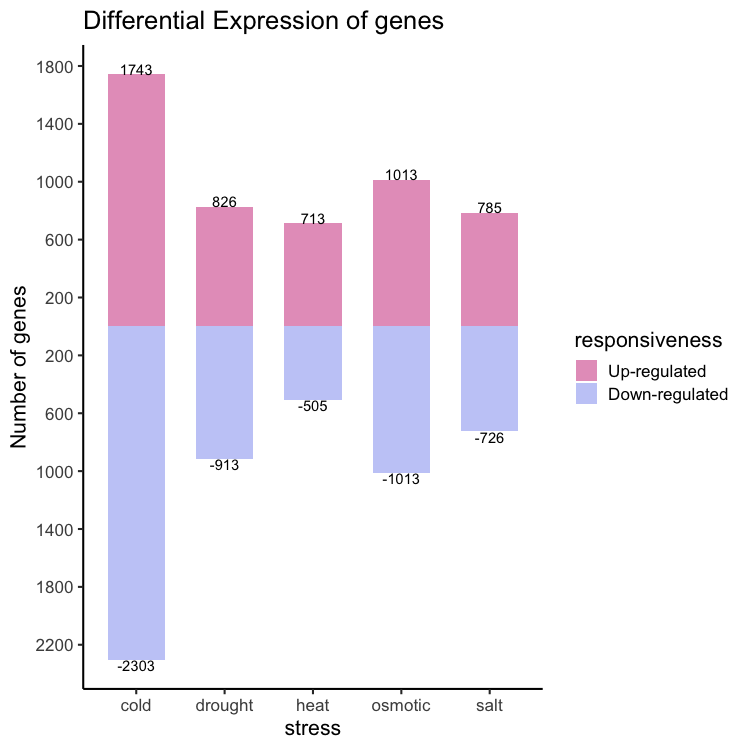

Creating a mirror plot

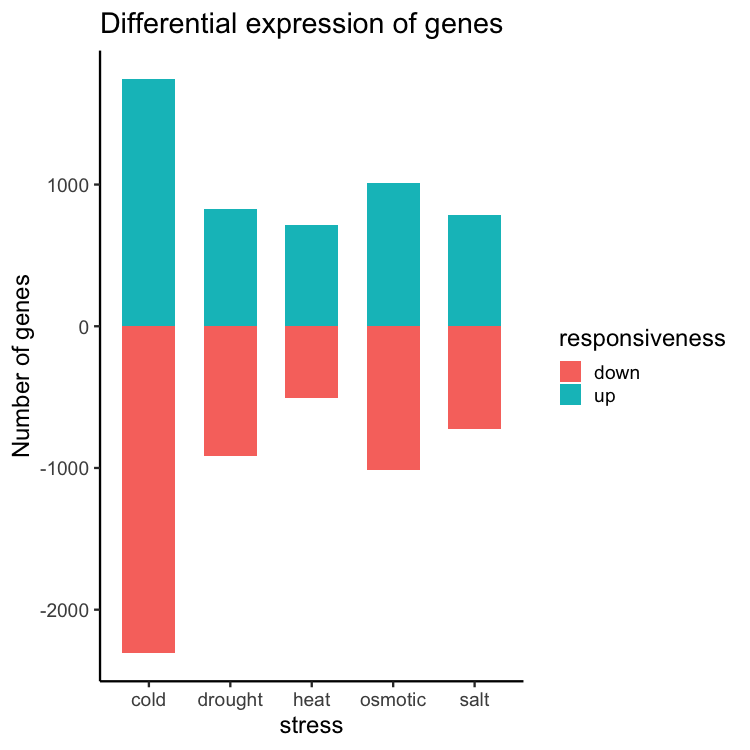

In this section we will see how to make the plot shown below.

Reading data in:

gene_nums_mirror <- read.csv( "../assets/data/up_down_gene_numbers.csv" )

gene_nums_mirror

stress responsiveness num_genes

1 cold up 1743

2 cold down 2303

3 osmotic up 1013

4 osmotic down 1013

5 heat up 713

6 heat down 505

7 salt up 785

8 salt down 726

9 drought up 826

10 drought down 913

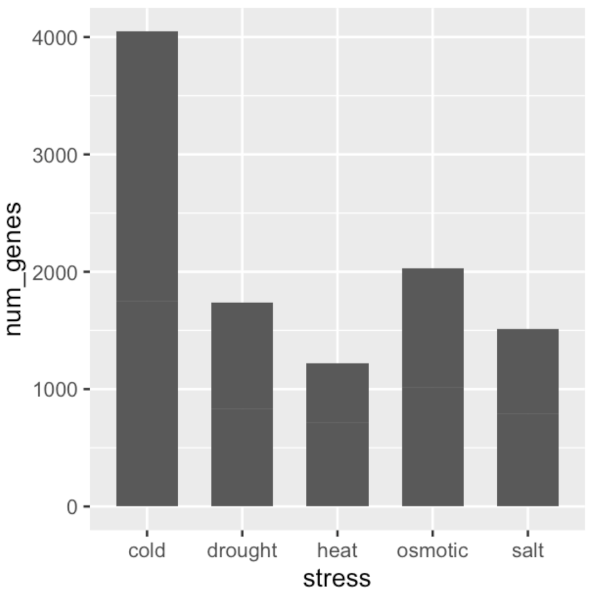

This data set has three columns and 10 rows. It is about differentially expressed genes under different stress conditions. So, let us start plotting with ggplot2.

#install.packages("ggplot2")

library( ggplot2 )

ggplot(data = gene_nums_mirror, aes(x = stress, y = num_genes)) +

# geom_bar(stat = "identity")

geom_bar( stat = "identity", position = "stack", width = 0.65 )

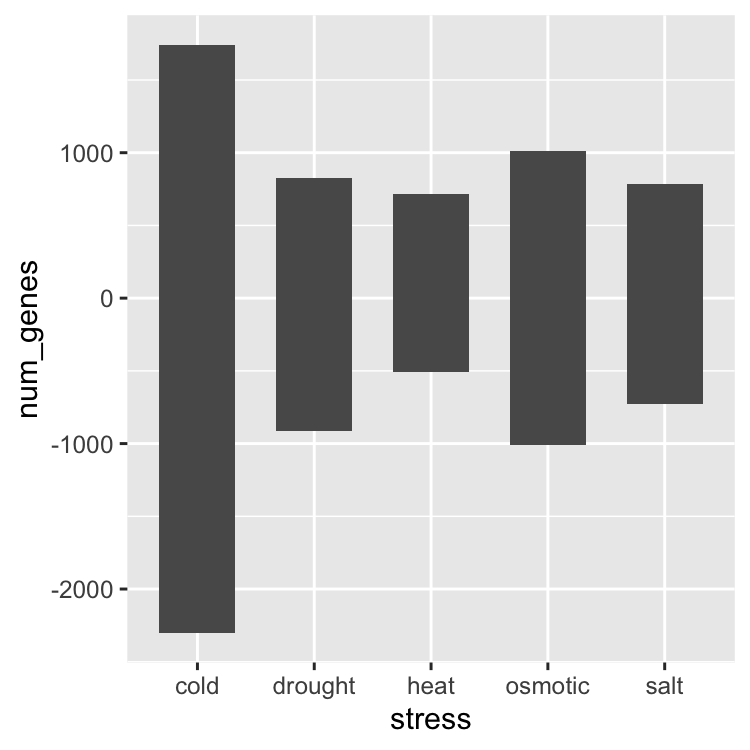

gene_nums_mirror$num_genes[gene_nums_mirror$responsiveness=="down"] <-

-gene_nums_mirror$num_genes[gene_nums_mirror$responsiveness=="down"]

gene_nums_mirror

stress responsiveness num_genes

1 cold up 1743

2 cold down -2303

3 osmotic up 1013

4 osmotic down -1013

5 heat up 713

6 heat down -505

7 salt up 785

8 salt down -726

9 drought up 826

10 drought down -913

ggplot(data = gene_nums_mirror, aes(x = stress, y = num_genes)) +

geom_bar(stat = "identity", width = 0.65)

ggplot(data = gene_nums_mirror, aes(x = stress, y = num_genes, fill = responsiveness)) +

geom_bar(stat = "identity", width = 0.65) +

theme_classic(base_size = 16) +

ylab("Number of genes") +

ggtitle("Differential expression of genes")

Re-ordering the levels: “up” first followed by “down”.

Re-ordering the levels: “up” first followed by “down”.

gene_nums_mirror <- dplyr::mutate(

gene_nums_mirror,

responsiveness = forcats::fct_relevel(responsiveness, "up", "down")

)

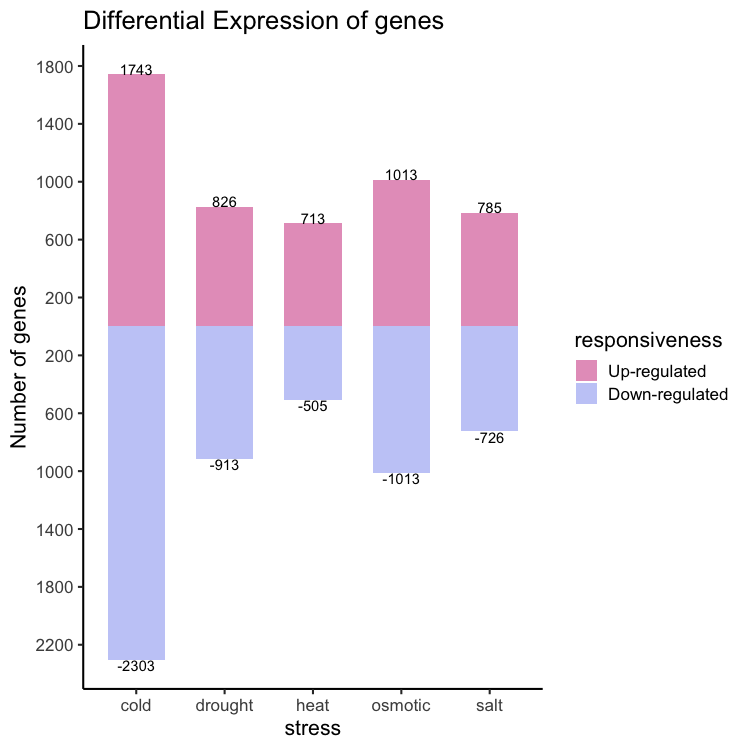

The final code snippet:

library( wesanderson )

ggplot(data = gene_nums_mirror,

aes(x = stress, y = num_genes, fill = factor(responsiveness, labels = c("Up-regulated", "Down-regulated")))) +

labs(fill = "responsiveness") +

geom_bar( stat = "identity", position = "identity", width = 0.65 ) +

ylab("Number of genes") +

theme_classic(base_size = 16) +

ggtitle("Differential Expression of genes") +

geom_text(aes(label = num_genes), vjust = ifelse(gene_nums_mirror$num_genes>0, 0,1), colour = "black") +

scale_y_continuous(breaks=seq(-3000,1800,by=400),labels=abs(seq(-3000,1800,by=400))) +

scale_fill_manual(values = wes_palette(n=2, name = "GrandBudapest2"))

Further Reading

Base R - core functionality for statistical computingBase R Graphics - traditional statistical graphing

ggplot2 - customizable graphs and charts

dplyr - data manipulation and transformation

tidyverse - advanced data manipulation, exploration and visualization

data.table - aggregation and manipulation of large data sets

Introduction to Julia programming

Julia setup: installation, environments and Jupyter integration

MODULE 06: High-Performance Computing (HPC)