If you are a beginner at Linux, it may be beneficial for you to start with the tutorials provided in section .

1. Bash expressions

The complete Bash Reference Manual is available at official documentation provided by www.gnu.org/.

1.1 Bash shortcuts

| symbol | description | usage example | reference |

|---|---|---|---|

~ |

a shortcut for the $HOME location in the file system |

cd ~ |

tilda expansion |

* |

denotes multiple unknown characters in a string | ls *.txt |

wild card expansion |

? |

denotes single unknown character in a string | for i in ??? |

question mark expansion |

$ |

to use/substitute the variable’s value | echo $variable |

dollar expansion |

COMMON USAGE of * and ? in regular expressions:

- in searching, e.g., with

greporfind - in listing file system, i.e.,

ls - in filtering files processed in the

forloop

1.2 Logical operators

The full list of Bash conditional expressions is provided in section 6.4 of bash manual available at gnu.org.

FILE OPERATORS

Below you have a quick overview for the most commonly used variants of file conditionals.

| FILE OPERATORS | definition |

|---|---|

| [ -a file ] | true if the file or directory exists |

| [ -d file ] | true if the directory exists |

| [ -f file ] | true if the regular file exists |

| [ -L file ] | true if the file is symbolic link |

| [ -w file ] | true if the file is writable |

| [ -x file ] | true if the file is executable |

| [ -s file ] | true if the file has a size greater than zero |

| [ file_1 -ot file_2 ] | true if file_1 is older then file_2 or if only file_2 exists |

STRING OPERATORS

Below you have a quick overview for the most commonly used variants of string conditionals.

| STRING OPERATORS | definition |

|---|---|

| [ -z string ] | true if the length of string is zero |

| [ -n string ] | true if the length of string is non-zero |

| [ string1 = string2 ] | true if the strings are equal |

| [ string1 == string2 ] | true if the strings are equal |

| [ string1 != string2 ] | true if the strings are not equal |

| [ string1 < string2 ] | true if string1 sorts before string2 |

| [ string1 > string2 ] | true if string1 sorts after string2 |

NUMERICAL OPERATORS

Below you have a quick overview for the most commonly used variants of numerical conditionals.

| NUMERICAL OPERATORS | definition |

|---|---|

| [ arg1 -eq arg2 ] | true if arg1 is equal to arg2 |

| [ arg1 -ne arg2 ] | true if arg1 is not equal to arg2 |

| [ arg1 -lt arg2 ] | true if arg1 is less than arg2 |

| [ arg1 -le arg2 ] | true if arg1 is less than or equal to arg2 |

| [ arg1 -gt arg2 ] | true if arg1 is greater than arg2 |

| [ arg1 -ge arg2 ] | true if arg1 is greater than or equal to arg2 |

^ The arg1 and arg2 may be positive or negative integers.

1.3 In-shell arithmetic

The full list of Bash shell arithmetic is provided in section 6.5 of bash manual available at gnu.org/.

OPERATORS

Below you have a quick overview for the most commonly used variants of arithmetic operators.

| OPERATORS | definition | OPERATORS | definition |

|---|---|---|---|

iter++ |

variable post-increment | iter-- |

variable post-decrement |

++iter |

variable pre-increment | --iter |

variable pre-decrement |

! |

logical negation | ~ |

bitwise negation |

** |

exponentiation | % |

remainder |

* |

multiplication | / |

division |

id++ |

variable post-increment | id-- |

variable post-decrement |

id++ |

variable post-increment | id-- |

variable post-decrement |

id++ |

variable post-increment | id-- |

variable post-decrement |

- |

substraction | + |

addition |

<= >= < > |

comparison | ||

&& |

logical AND | || |

logical OR |

^ The operators are listed in order of decreasing precedence.

INTEGER LIMITATIONS

- division by 0 is prohibited

- floating-point arithmetic is not directly supported

ARITHMETIC EXPANSION

The arithmetic expansion $(( expression )) substitutes the results of an evaluated expression into a variable. [source: gnu.org]

echo $((1+2))

echo $((x=1, y=1, x+y))

n=1;

echo $((++n))

let command

k=1;

let k=$k + 2

bc command

(supports floating-point up to 20 decimal places)

echo "1.5 + 2.0" | bc -l

awk command

(supports floating-point up to 6 decimal places)

awk 'BEGIN { x = 1.5; y = 1.5; print "x + y = "(x+y) }'

perl command

(supports floating-point up to 20 decimal places)

perl -e 'print 1.5+2.0'

1.4 In-line substitution

- useful as in-line generators of arguments for for loop

BRACE AUTOCOMPLETION

A. Use the array of strings

(note that there are no spaces)

echo "Hello "{Universe,World,Contry,City,Friend}

B. Use the array of auto-generated integers

echo "Count "{0..10}

C. Use combinations of many arrays

echo {a,b}_{0..5}

COMMAND SUBSTITUTION

Use `command` or an equivalent $(command) syntax to create the array of items on-the-fly.

for i in `seq 10`; do echo $i; done

It works for any command enclosed in the `` or $(). The most comman usages are generating array of integers with seq command or creating an array of strings cat from the one-column file.

for i in `seq 1 2 10`; do echo $i; done

for i in $(seq 1 2 10); do echo $i; done

for i in `cat one-column-file`; do echo $i; done

for i in $(cat one-column-file); do echo $i; done

2. Bash statements

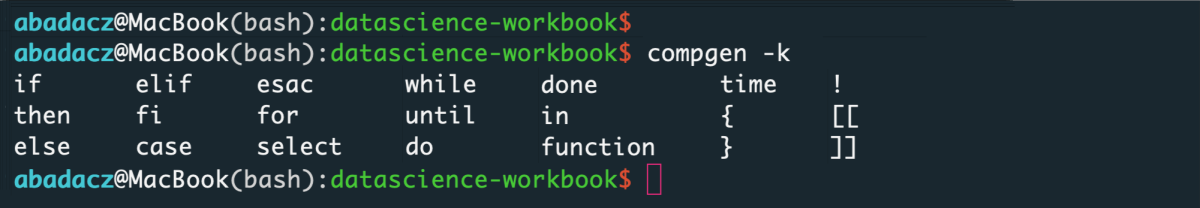

Bash is a Unix shell that allows you to call processes on the computing machine directly in the command line. In addition to a set of built-in commands (check them with the compgen -b command) that perform predefined tasks, you can create your own algorithms in the Bash shell. To give a structure to the algorithm, Bash uses several keywords and special characters that are interpreted by the Unix shell. The set of these expressions is referred to as Bash statements and can be understood as a set of universal building blocks that you can use to build your own customized algorithm.

You can view the available Bash statements on the command line using the compgen command with the k flag:

compgen -k

There are about twenty-some Bash statements, which can be further divided into several groups, including loops, conditionals, the action operators, and others. The table below contains the syntax, type, and definitions of the most common Bash statements. Explore additional column with notes to gain an idea of when to use different syntaxes. In the following subsections, we will discuss the usage of Bash statements following real-life examples.

| statement | type | definition | notes |

|---|---|---|---|

for |

loop | iterating over each item in the list | use if you want to execute commands in order for all items in the list YES, nested loops are allowed |

while |

loop | iterating as long as the condition is true | use if you want to perform a certain number of iterations, such as reading a file line by line YES, infinite loop is possible, try while : |

until |

loop | iterating as long as the condition is false | use if you want to perform an infinite number of iterations terminated by meeting a condition the frequency of execution of the condition is usually adjusted with the sleep command |

select |

loop | selective iterating over options in the menu | use to give the user the interactive option to select items from a menu (predefined list) |

if ... fi |

conditional | considering the first condition | use if for the first condition and fi after the last condition |

elif |

conditional | considering the next condition | use for the second and following conditions |

else |

conditional | operation for all other scenarios | if no condition was met then follow these commands |

case...esac |

conditional | matching condition for query variable | use when all of the conditions depend on the value of the same variable |

in |

iteration operator | iterating in the for and select loops |

for loop syntax:for item in {1..5}; do commands; doneselect loop syntax: select item in {1..5}; do commands; done |

do ... done |

action operator | encapsulating the contents of the loop | use the syntax: do commands; done in a loop syntax |

then |

action operator | executing commands if condition is true | use the syntax: if condition; then commands; fi |

break |

action operator | terminating the current loop | use to terminate a loop at this point and go straight to the commands that follows |

continue |

action operator | moving to the next iteration in the loop | use to skip the commands in the current iteration and go straight to the next |

function |

function construct | keyword that precede the creation of a function | to define a new function available in the bash shell, use syntax: function custom_name {commands} |

time |

shell command | keyword that estimates the execution time | use the time keyword before executing the command e.g., time ls \| grep "PNG" |

test |

shell command | keyword that checks the logic of the condition | e.g., if test $x -gt $yreturns true when x is greater than y |

[ ... ] |

logic construct | syntax that checks the logic of the condition | the equivalent to the test command e.g., if [ $x -gt $y ] |

[[ ... ]] |

logic construct | syntax that checks the logic of the condition | helps to avoid logic errors in Bash;&&, \|\|, < and > operators work |

{ ... } |

array builder | syntax that allows to build an array of items | it can be a predefined list of strings or numbers e.g., {one,two,three,four,five}it can be an automatically generated list of integers e.g., {1..5} , use two dots between the numbers |

FOR each item loop

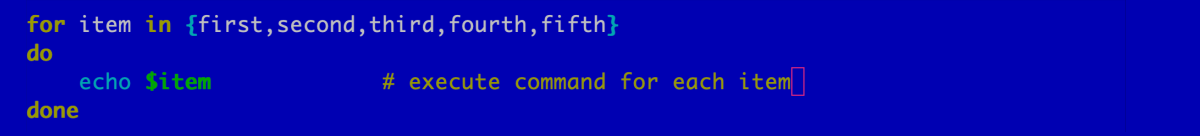

FOR loop provides the easiest way to iterate over the ordered list of items (strings or integers) and execute the set of commands for each.

The syntax is made up of several keywords reserved for the bash shell and customized arguments provided by the user. When a statement is defined in a script file, it usually has a block structure, where the contents encapsulated in do ... done syntax is indented by a fixed number of spaces, usually 4 or 2 for more nested algorithms.

for item in {first,second,third,fourth,fifth}

do

echo $item

done

In some intra-terminal text editors such as mcedit (part of the midnight commander package), individual components of bash syntax are highlighted in different colors, making it easier to follow the correctness of the code.

The for, in, do, done are fixed bash statement elements, performing specific functions that are interpreted by the Unix shell (for details see table above). The word or character occurring between for and in is a user-provided variable that specifies the name of the iterator. Usually it is the letter i, but it can be any string, which will specify the type of iterated values. In successive loop cycles (iterations), the iterator takes the next value from the array and executes for it the commands contained in the do ... done code block.

Avoid naming iterators and other variables with a single character since there are a finite number of letters. Overriding the iterator value inside the loop could result in algorithm failure.

Note: The more meaningful the iterator name reflecting the type of items, the better readable the code for other programmers.

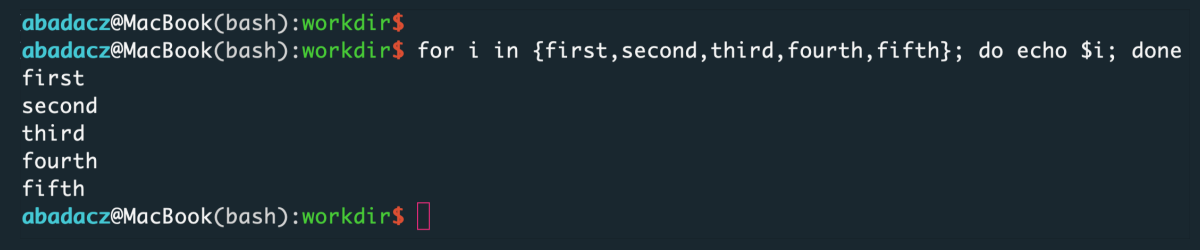

You can also use FOR loop syntax directly in the command line as a one-liner, to see the result immediately:

for item in {first,second,third,fourth,fifth}; do echo $item; done

Remember to always separate consecutive statement elements with a semicolon ; in single-line syntax.

ITERATION VARIANTS

(VARIANTS OF A FOR-LOOP SYNTAX)

A. Iterate over strings given directly (separated by spaces):

for item in item1 item2 item3 item4 item5; do

echo $item

done

B. Iterate over strings given in an array (separated by commas without spaces):

for item in {item1,item2,item3,item4,item5}; do

echo $item

done

C. Iterate over integers given in an array (separated by commas without spaces):

for item in {1,2,3,4,5}; do

echo $item

done

D. Iterate over integers generated automatically using an array:

for item in {1..5}; do

echo $item

done

You can add a step as a third argument to the array syntax, e.g., {1..10..2} to iterate over odd numbers. {$START..$END..$STEP}. Note, however, that you must define them in advance and assign them a value before usage.

E. Iterate over integers generated automatically using sequence:

for item in `seq 1 1 10`; do

echo $item

done

The syntax for generating integers in a sequence is seq START STEP END or $(seq START STEP END).

If your step is equal to one, you can skip the middle argument.

F. Iterate over integers generated automatically using incrementation:

for ((item=1;item<=5;item++)); do

echo $item

done

You can start with a large integer and count down using the decrementing ( item-- ).

G. Iterate over any items stored in the one-column file:

for item in `cat file`; do

echo $item

done

That syntax cat file is useful when iterating over a long list of strings that can be read directly from a one-column file.

H. Iterate over items resulting from the command:

for item in `ls | grep "txt"`; do

echo $item

done

That the custom command syntax, such as ls | grep "txt", is useful when iterating over a filtrated list of files stored in current directory (or any location in a file system).

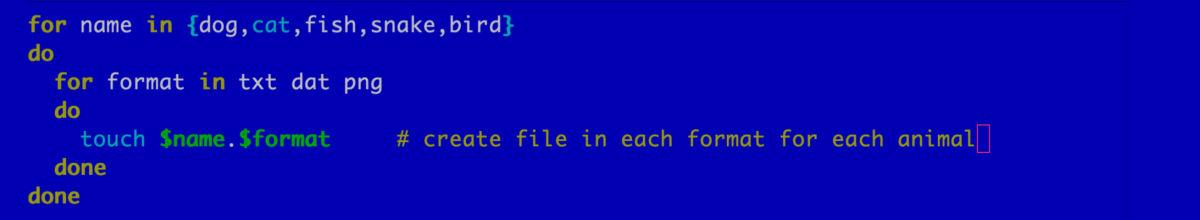

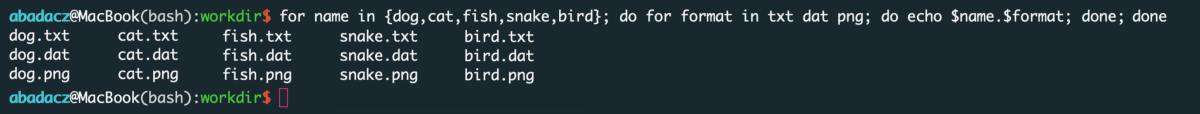

NESTED LOOPS

When you want to iterate on an each-to-any basis over two or more sets of features, such as creating a set of files with specific names in 3 different formats, use nested FOR loops.

# script variant

for name in {dog,cat,fish,snake,bird}; do

for format in txt dat png; do

echo $name.$format # replacing 'echo' with 'touch' will create empty files

done

done

The same algorithm can be executed as a one-liner directly in the command line.

# one-liner variant

for name in {dog,cat,fish,snake,bird}; do for format in txt dat png; do echo $name.$format; done; done

Use a template for 2 nested FOR loops

for item1 in {ARRAY-OF-ITEMS}; do

for item2 in {ARRAY-OF-ITEMS}; do

<COMMANDS>

done

done

As long as you are diligent in properly nesting consecutive for-do-done statements, you can make as many inner loops as you want.

Note: Remember that the inner loop must always be closed with the done keyword before the more outer loop.

…from the previous subsection in this tutorial about other iteration options available besides using arrays.

WHILE true loop

WHILE loop iterates as long as the user-provided condition is true. So, use while loop statement if you want to perform a certain number of iterations, whether that number is known or not. Syntax is made up of while keyword reserved for the bash shell and customized condition provided by the user in square brackets. Similarly to other Bash loops, the commands (dependent on loop condition) are encapsulated in the do ... done block of code.

Use a template for WHILE loop

while [ <CONDITION> ]

do

<COMMANDS>

done

Commands are executed as long as the user-provided condition evaluates to true. Note that the condition is evaluated at the beginning of each iteration, so before executing the block of commands. The conditional could involve operators on files, strings comparison, the numerical equivalence of integer iterator, or infinity condition. To learn more about Bash logical operators, revisit section 1.2 in this tutorial. Below you can find some handy tips for different conditionals:

| FILE OPERATORS | definition |

|---|---|

| while [ -a file ] | execute if the file or directory exists |

| while [ -d file ] | execute if the directory exists |

| while [ -f file ] | execute if the regular file exists |

| while [ -L file ] | execute if the file is symbolic link |

| while [ -w file ] | execute if the file is writable |

| while [ -x file ] | execute if the file is executable |

| while [ -s file ] | execute if the file has a size greater than zero |

| while [file_1 -ot file_2] | execute if file_1 is older then file_2 or if only file_2 exists |

The three most common usages of while loop are iterating for as long as the specific iterator value is not reached, reading the file line-by-line to the end of the file, and for creating an infinite loop that runs in the background and monitors any process.

ITERATE WHILE VALUE

Let’s assume that you know the upper threshold of a certain parameter and you know that once this value is exceeded, the analysis makes no further sense, e.g., you know that the percentage of component X in the mixture cannot be higher than 50%. You can use a while loop to test the properties of your mixture, increasing the content of component X every 1% until you reach the limit value.

max_val=50

val=0

while [ $val -le $max_val ]

do

echo Percentage: $val

# run your program: program -arg $val > output_$val

((i++))

done

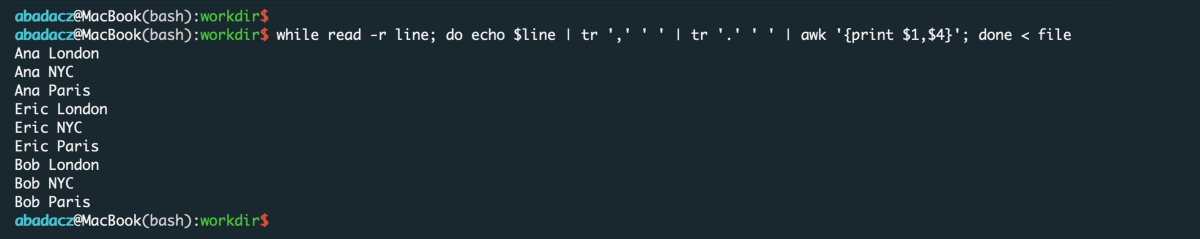

READ FILE LINE-BY-LINE

Let’s first create the simple file with several lines of content:

# script variant

for i in {Ana,Eric,Bob}; do

for j in welcome; do

for k in {London,NYC,Paris}; do

echo $i", "$j" to "$k"." >> file;

done;

done;

done

# one-liner variant

for i in {Ana,Eric,Bob}; do for j in welcome; do for k in {London,NYC,Paris}; do echo $i", "$j" to "$k"." >> file; done; done; done

You can preview the results saved into a file using less file command:

Once we have a file with some content, we can read it line-by-line with a while loop and derive from each line the name and the city.

filename=./file

while read -r line; do

echo $line | tr ',' ' ' | tr '.' ' ' | awk '{print $1,$4}'

done < "$filename"

The filename variable stores the name of recently created file.

If you work by executing scripts rather than typing directly on the command line, it’s a good practice to create a variable that stores the path to the input file. Then running the same script for a different input only requires substituting the path or a filename at the top of the file.

In this case, the condition for the while loop is replaced by the read command followed by the name of the variable in which the loaded content is stored. By default, the read command reads a single line from a bash shell or, as in this example, a single line from a text file. The text file is inserted into the loop using < stream redirection. Inside the do ... done syntax it is possible to parse a single line from a file.

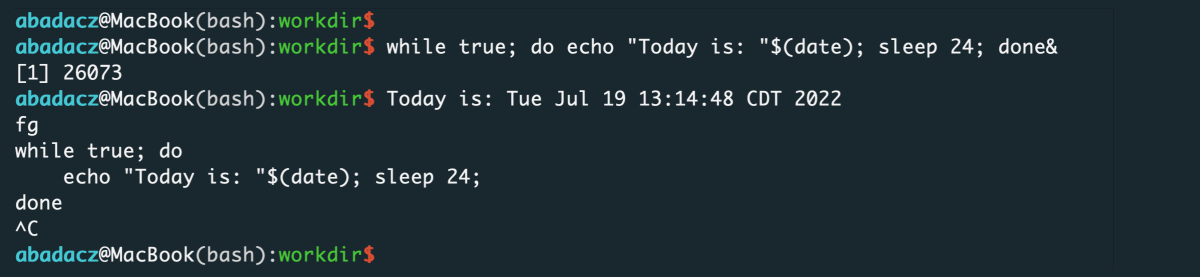

INFINITE LOOP

Imagine that you never turn off your computer, and every day at the same time, you want to perform a certain process, such as checking the date. You can easily do this with a while loop and an infinity condition while : or while true. After executing the process once, you can manage to silence the loop activity for the next 24 hours with sleep command. Then the commands in the loop will be executed again.

while :

do

echo "Today is: "$(date)

sleep 24h

done

If you don’t want to have the terminal blocked with a process running indefinitely, move that process to the background using & at the end of the command.

while true; do echo "Today is: "$(date); sleep 24h; done&

To restore this process to foreground, use the fg command. Then you can end the loop definitively using CTRL+C if it is no longer needed.

UNTIL false loop

UNTIL loop iterates as long as the user-provided condition is false. So, use until loop statement if you want to perform a given number of iterations. Syntax is made up of until keyword reserved for the bash shell and customized condition provided by the user in square brackets. Similarly to other Bash loops, the commands (dependent on loop condition) are encapsulated in the do ... done block of code.

Use a template for WHILE loop

until [ <CONDITION> ]

do

<COMMANDS>

done

Commands are executed as long as the user-provided condition evaluates to false. Note that the condition is evaluated at the beginning of each iteration, so before executing the block of commands. The conditional could involve operators on files, strings comparison, the numerical equivalence of integer iterator, or infinity condition. To learn more about Bash logical operators, revisit section 1.2 in this tutorial.

The most common uses of the until loop include iterating until the iterator reaches a given value, or checking the status of a specific process.

ITERATE UNTIL VALUE

Suppose you want to perform an optimization using program X, which will use the results from the previous cycle for each subsequent iteration. You know that this program converges to the best results in 10 iterations and further calculations make no improvement. An effective solution, is to enclose this procedure in a loop until, where the loop will terminate when the iterator value reaches a predefined maximum value, max_iter.

If you do not know after how many cycles the optimization will be achieved, you can set to replace the iter variable with score and terminate when the expected threshold of improvement between iterations is reached.

max_iter=10

iter=0

until [ $iter -gt $max_iter ]

do

echo Iteration: $iter

# run your program and redirect output to a file: program -i file_$iter-1 -o file_$iter

((iter++))

done

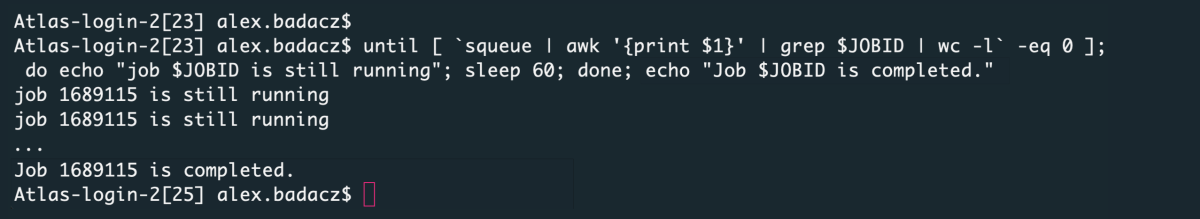

STOP ONCE SUCCESS

Let’s create a script that checks the status of running processes with the squeue command and will notify you when your queued task is finished. The until loop will be terminated when the JOBID of your task is no longer visible in the queue on the computing cluster. However, as long as the task is running, comparing the number of matching JOBID to zero will return false in the conditional and the loop will still be active.

JOBID=1689115

until [ `squeue | awk '{print $1}' | grep $JOBID | wc -l` -eq 0 ]

do

sleep 60

done

echo "Job $JOBID is completed."

if-elif-else-fi conditional

In most cases, iterating through all the possibilities is computationally inefficient and time-consuming. With help comes Bash conditionals. This is a logical construction that allows you to consider different options and execute commands only when certain conditions are met. This applies when you want to process only files of a certain size or process further only significant values of loaded data. It could also be that for various categories in your dataset you want to use different parameter values. Other times you may want additional analysis for a certain subset of the data, while everything else is calculated in the default way. All these cases suggest using if-elif-else-fi conditional for Bash-based approaches.

The most external and mandatory part of the syntax is the bracket if ... fi.

The if takes as an argument a condition defined in square brackets (single or double) or must be preceded by the keyword test. The test can be considered equivalent to the [ ] syntax, while the double brackets [[ ]] are a more robust solution that allows defining multiple conditions connected by && (and) or || (or) operators. The reserved word then in bash indicates where to trigger commands if the condition is met.

if [ <condition> ]; then

<COMMANDS>

fi

if [[ <condition_1 && condition_2 > ]]; then

<COMMANDS>

fi

The following can be used as conditions: operators on files, strings comparison, the numerical comparison of iterator to integer value. For more on the comparing conditions and available operators, see section 1.2 of this tutorial.

touch file; file=file

if [ -f $file ]; then echo $file; fi # execute if $file is a regular file

val="word"

if [ $val = "word" ]; then echo $val; fi # execute if $val is a string "word"

num=20

if [ $num -gt 5 ]; then echo $num; fi # execute if $num is numerical and greather than 5

The above examples prove that the echo command is executed when the condition is met. But what if we want to execute another command if the condition is not satisfied? In this case, the syntax should be expanded with additional keywords elif and/or else. While elif can be used multiple times to define further specific conditions, else occurs once, always at the end of the syntax just before closing with fi. That is because else covers all cases not directly provided in condition variants, or in other words, executes a default set of commands in case all conditions are false.

num=2

if [ $num -gt 10 ]; then

echo "The value "$num" is greater than 10"

elif [[ $num -eq 4 || -gt 5 ]]; then

echo "The value "$num" is equal to 4 or greter than 5 but lower than 10"

else

echo "The value "$num" is lower than 4"

fi

Be precise when you define conditions.

In particular, take care of the order of the conditions being checked in the single syntax if .... fi. That is important because the else condition is executed only if all of the above return false. elif variant will not return numbers greater than 10, even though they will be greater than 5, because they will already be returned in the if condition.

Note: Remember, in the given syntax of if ... fi commands are executed only for the first satisfied condition of the considered variable.

Use the template of if-elif-else-fi conditional

if [[ <condition(s)> ]]; then

<COMMANDS>

elif [[ <condition(s)> ]]; then

<COMMANDS>

else

<COMMANDS>

fi

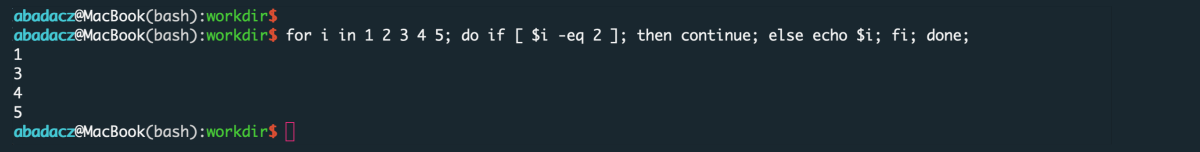

continue to next iteration

The continue statement terminates the current iteration, skipping the remaining commands in the current loop (if nested), and passes the execution mode to the next iteration of a current loop. That means no more than premature termination of the single iteration in a given loop. Further iterations in this loop, as well as remaining commands in the other loops are not altered by this event.

for i in 1 2 3 4 5; do

if [ $i -eq 2 ]; then

continue #-------- remaining code in this iteration (i=2) will NOT be executed

else

echo $i

fi

done

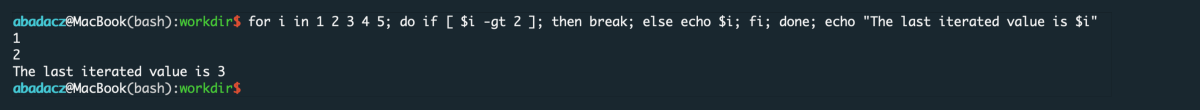

break the loop

The break statement terminates the loop at the current iteration, exactly in the place where the break keyword occurs in the block of code. It means that commands remaining in the loop will not be executed, and the loop will not continue to iterate. The execution mode will be moved just outside the loop. Thus, the commands following the done keyword will further execute.

for i in 1 2 3 4 5; do

if [ $i -gt 2 ]; then

break #-------- remaining code in the FOR loop and IF-ELSE-FI conditional will NOT be executed

else

echo $i

fi

done #-------- commands below the line will be executed after break statement

echo "The last iterated value is $i"

Usually break is placed in the conditional if ... fi,

but this statement is a universal terminator for all bash loops, including for, while, until and select. break terminates the loop in which it occurs.

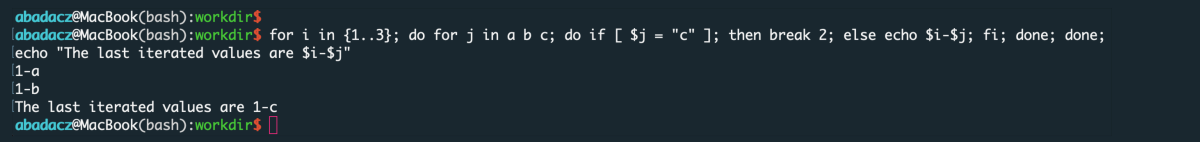

If it is an inner loop in a nested schema, by default it only terminates the inner loop. To terminate parent loops from within the inner loop, use the break -n command, where n is the index of the higher level loop counted from the loop in which the break resides. The default is n=1 and applies the termination to the current loop.

Let’s terminate the outer loop from the inner loop level:

for i in {1..3}; do

for j in a b c; do

if [ $j = "c" ]; then

break 2 #-------- remaining code in both loops will NOT be executed

else

echo $i-$j

fi

done

done #-------- commands below the line will be executed after break statement

echo "The last iterated values are $i-$j"

3. Bash scripting

3.1 In-line scripting

It is good to know that almost any bash script saved in a file can be copy-pasted into the command line and executed at the press of enter. The only limitation is the size of this script. The invaluable advantage of storing the script in a file is also the knowledge retention from the project and reusability. Nevertheless, even multi-nested loops can be effectively written and executed directly on the command line. This approach is useful in daily workflows and helps prevent easily reproducible code from cluttering up storage space. Note also that usually the last 500 commands are kept in the shell history, so it is easy to retrieve longer one-liners used a few days earlier.

Remember to separate the elements of bash statements with a semicolon ; when creating one-liners on the command line.

3.2 Setting up the script

If you don’t know how to create a file from the command line or redirect a command stream to a file, I recommend that you start with the and .

If you are not familiar with any of the basic text file editors in the terminal, such as nano, vim, or mcedit, take a look at the .

HEADER

Use #!/bin/env bash syntax at the top of your script file instead of #!/bin/bash as a more robust solution to keep a stable Bash environment. Applying the first statement will provide you with the default version of the program (e.g., bash or python) for your current environment.

Follow the user’s discussion at unix.stackexchange.com and stackoverflow.com to learn more.

VARIABLES

A. FROM ARGUMENT: Use $1 variable to pass the value of the first argument provided after script name when executing.

B. GLOBAL: The global variables are set outside the loop and exist after the loop ends.

C. ITERATIVE: The iterative variables are those that store the current value of the loop iterator, regardless of whether they are strings read from a file or numbers incremented/decremented in successive loop cycles. The correct value usually disappears after leaving the loop and should not be further used.

D. LOCAL: The local variables are temporary by design and they usually exist/are accessible only in the loop or conditional where they were created.

ALGORITHM

A. PIPE-linked stream of commands

cat file | grep "keyword" | tr '-' ' ' | awk '{print $2,$4,$6}' | sort -nk1 | uniq

Note that the result of the command stream can be redirected to:

- a file, e.g.,

command1 | command2 > file - to a variable, e.g.,

variable=`command1 | command2` - or displayed on the screen, e.g.,

command1 | command2

B. Encapsulation in a loop

for i in {0..10}; do

touch file-$i;

done

C. Conditional execution of commands

if [ $variable -gt 5 ]; then

echo $variable

else

break

fi

D. Various types of outputs

TEXT OUTPUTS

k="Hello World!"

echo $k

GRAPHICAL OUTPUTS

Encapsulating Gnuplot script in a bash for loop allows for returning image files all at once for multiple inputs.

#!/bin/bash

# BASH VARIABLES

output="simple_graph"

format=png

for i in *.txt; do

k=`echo $i | tr '.' ' ' | awk '{print $1}'`

gnuplot -persist <<- EOF

# LAYOUT SETTINGS

set terminal '$format'

set output '$output-$k.$format'

# PLOTTING COMMAND

plot '$i' u 1:2 with points

EOF

done