What is Unix?

UNIX is an operating system (OS) for computer devices providing the command-line interface (CLI) for convenient and efficient programming. The modern Unix OS variants are multi-tasking and multi-user, allowing for sharing computing resources among many users at the same time �. They are also portable, supplying the operating system for personal computers, computing clusters, database & web servers, and high-end workstations. The open-source Unix distributions within the Linux family include Ubuntu, Debian, RHEL (Red Hat Enterprise Linux), Linux Mint, Fedora, CentOS, OpenSUSE, Manjaro, and Arch Linux. Besides GNU/Linux there are other varieties of UNIX such as Sun Solaris, macOS X, IBM AIX, Darwin OS, and FreeBSD OS (some of them are not free).

Figure 1. Logos of the most popular Linux distributions, all based on the Unix command-line interface.

Standard features of Unix-like OS include: security, reliability, and scalability with easy batch processing & time-sharing configuration that supports hundreds of users at the same time by means of multiprogramming and multi-tasking �.

Can I learn Unix?

Yes!

Absolutely. It is just another way of operating your computer.

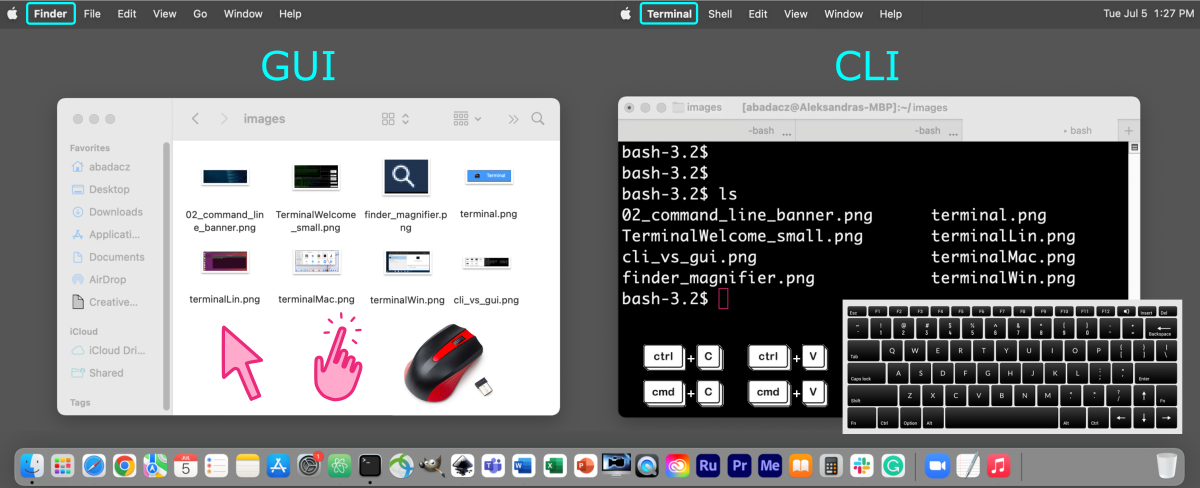

The main difference between using Linux and Windows/Mac is that you use the command-line interface (CLI) and keyboard to execute programs instead of using a graphical user interface (GUI) and mouse. However, modern Unix variants of the Linux family provide a user-friendly graphical-like interface for personal computers with desktop.

Figure 2. In the graphical user interface (GUI, on the left), you use a mouse to navigate the file system and execute applications by clicking, while in the command-line interface (CLI, on the right), you type text-like commands on your keyboard to do the same (and much more!).

In the terminal, get used to using only the keyboard and abandon the use of the mouse.

Keyboard shortcuts

Below is a list of handy keyboard shortcuts to make it easier for you to switch from the mouse to the keyboard. You will realize quickly how much faster and more convenient your daily work will be.

Manage Terminal windows & tabs

| shortcut | on macOS | operation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ctrl + T | cmd + T | open new terminal tab | |

| ctrl + W | cmd + W | close curent terminal tab | |

| cmd + opt + W | close other tabs | ||

| cmd + shift + W | close the terminal window | ||

| ctrl + tab | ctrl + tab | go to the next tab | |

| ctrl + shift + tab | ctrl + shift + tab | go to the previous tab | |

| cmd + D | split window into two panes | ||

| cmd+shift+D | close split pane | ||

| ctrl + (+) | cmd + (+) | make fonts bigger | |

| ctrl + (-) | cmd + (-) | make fonts smaller | |

| cmd + home | scroll to top | ||

| cmd + end | scroll to bottom | ||

| cmd + page-up | move page up | ||

| cmd + page-down | move page down |

Edit a command line

| shortcut | on macOS | operation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ctrl + A | move the cursor to the beginning of the line | ||

| ctrl + E | move the cursor to the end of the line | ||

| ← or → | ← or → | use arrow keys to move backward / forward one character | |

| opt + ← or → | move backward / forward one word | ||

| ↑ or ↓ | ↑ or ↓ | use up-down arrows to browse the recent command history | |

| ctrl + U | delete all characters in the line | ||

| ctrl + L | ctrl + L | clear the content in the terminal tab | |

| ctrl + C | cmd + C | copy selected item | |

| ctrl + V | cmd + V | paste selected item | |

| ctrl + X | cmd + X | cut selected item | |

| ctrl + A | cmd + A | select all | |

| ctrl + Z | cmd + Z | undo / cancel / stop running process | |

| ctrl + F | cmd + F | find / search in the current tab | |

| ctrl + R | ctrl + R | search in the command history by keyword | |

| ctrl + S | cmd + S | save | |

| ctrl + P | cmd + P | ||

| ctrl + O | cmd + O | open |

More shortcuts for specific version of macOS you can find at Apple support page.

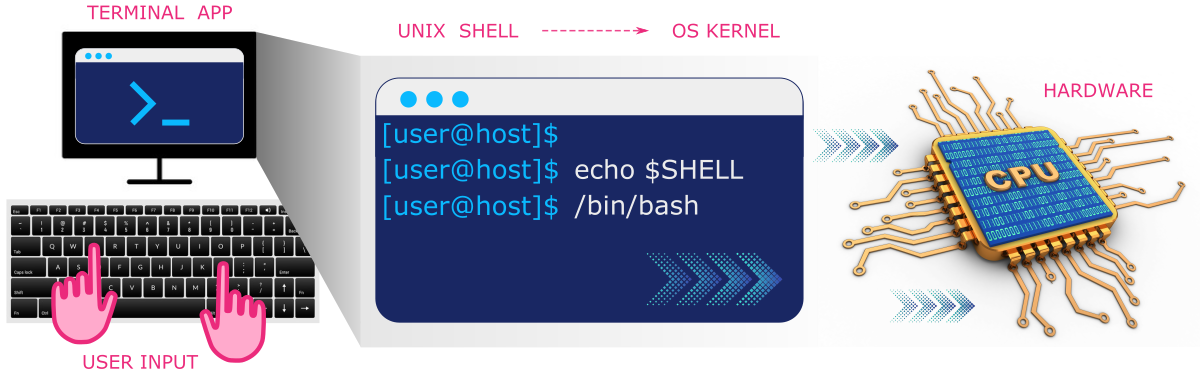

1. Unix Shell

A Unix shell is a command-line interpreter that translates the user-provided text-like commands to a form understandable by the kernel of a computer operating system. A kernel is a low-level program in the core of operating system that communicates with the hardware. The shell serves as both a language providing built-in commands and a scripting language giving the user more freedom to build custom pipelines. Thus, the shell is launched in the terminal window, right after the user opens it. In the most popular Linux distribution, such as Ubuntu, Bash (Bourne-Again Shell) is a default pre-installed Unix shell. However, on high-performance computing infrastructures (HPC) the C-shell, such as csh or tcsh may be preffered.

Figure 3. The layered structure of user-computer communication using a command-line interface (CLI). The user uses a terminal app to enter text-like commands into the Bash shell that interprets them into the binary language understandable by the operating system kernel, which triggers the execution of processes on the computer hardware.

1.1 Unix Shell Terminology

In the table below, you can find a concise summary of terminology related to working on the command line in the Unix shell. Pay special attention to the notes column, as you will find many valuable tips & tricks there.

| TERM | DEFINITION | NOTES |

|---|---|---|

| terminal | program that provides the user interface for the Unix shell | |

| shell | command line interpreter | the most popular is sh (known as Bash) shell, but some power users prefer alternatives such as csh (C shell), ksh (Korn shell), zsh, (Z shell) |

| kernel | the core of the computer oparating system communicating with hardware | |

| user | the name of a user currently logged in to the system | |

| root/sudo | the super-user with admin privileges | |

| path | location in the file system | |

| filename | the name of a file | In Unix it is better to not include spaces in names for directories. The underscore “_” can be used to replace any spaces you might want. |

| variable | a word that is a reference to a stored value | to retrieve a value you must prefix a variable name with $e.g., variable="hello world!" and then echo $variable |

| command | a build-in word that is interpreted by a shell and triggers the execution of a specific process | use compgen -c to list all executable commands; other flags include -a filters aliases, -b filters shell built-ins, -k filters elements of shell syntax (for, if, then, etc.) |

| alias | a user-defined text shortcut for a more complex set of commands | aliases can be defined in the .bashrc file |

| script | a more complex set of commands stored in the file; often encapsulated within a loop syntax and executed under the conditionalities of the algorithm | - to run a script saved to a file you need give it executable permissions using chmod command - commands stored in a file can also always be run by preceding the file path with a dot-and-space syntax: . path/script.sh |

| environment | the configuration of settings in a shell | to have various environments needed for specific analyses, you can create many virtual environments and switch between them |

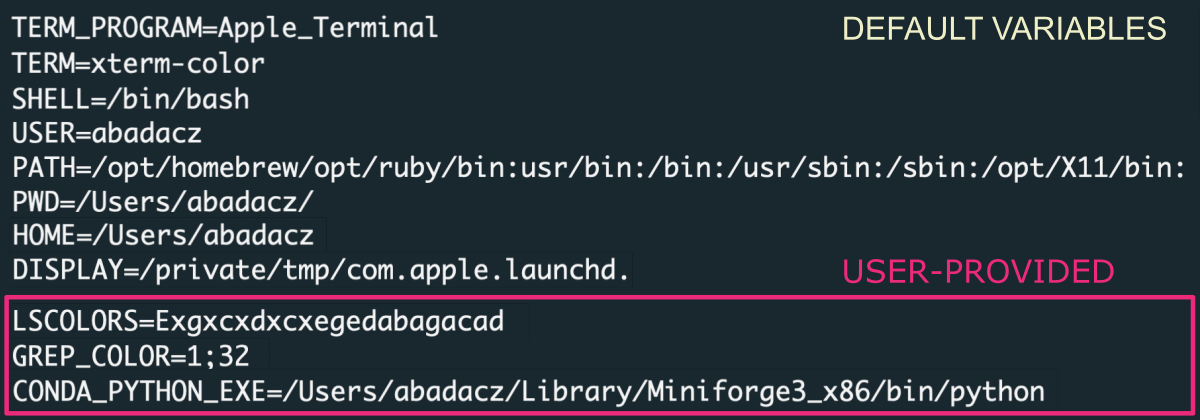

1.2 Unix Shell Variables

The Unix shell has a default configuration which can be further adjusted by a user. The settings together with available commands, loaded modules, and created aliases constitutes an environment. For getting more information about the current state of the shell’s environment, you can type env, which lists all the variables currently set.

env

Figure 4. The environment in the Unix shell is determined by the configuration of built-in variables such as $HOME or $USER, and user-provided variables that adapt the environment to its needs (e.g., $LSCOLORS sets colors for listing files in a directory).

If you want to know specifically about a variable, you can get the value by typing in the command line echo ${VARIABLE}, for example:

echo $SHELL

echo $USER

echo $HOME

Some variables available in the shell by default are:

| VARIABLE | DEFINITION |

|---|---|

TERM |

terminal |

SHELL |

Shell type (bash, csh, ksh, etc.) |

USER |

username |

HOSTNAME |

hostname for the system |

HISTFILE |

file where the history is saved |

HISTSIZE |

number of commands saved in history |

HOME |

path for home |

PWD |

present working directory |

PATH |

paths where executables are stored |

EDITOR |

default text editor |

DISPLAY |

where to route the display |

More about user-provided variables you will learn in the section 3. Unix Shell Configuration of this tutorial.

2. HOME directory

The HOME directory is the default localization in the file system once you log in on the remote computing machine or open the terminal window on your local computer. Usually, it is called with the {username}, especially on a multiuser infrastructure. The parent directory gathers the home directories of all users present on a given operating system and is typically named Users or home. The latter is located in the ROOT, i.e., outer-most layer of the hierarchical file system. You can go there directly by prefixing the directory name with / (or \ on Windows).

Thus, your HOME directory is accessible on the path:

/home/{username}for Linux operating system/Users/{username}for Mac operating system\Users\{username}for Windows operating system

Note that backslash is used on Windows!

Few more tips on how to navigate into the HOME or root directories:

cd / # navigates you into the ROOT directory

cd ~ # navigates you into the $HOME directory

cd .. # navigates you UP one directory level

The table below shows the structure of a file system for various operating systems. $HOME corresponds to the directory called with custom {username} (i.e., value of $USER variable). The configuration of the Unix shell can be adjusted in the hidden .bashrc file.

| Linux on HPC | Linux on local machine | macOS | Windows |

|---|---|---|---|

| ROOT/ |- home/{username}/ |- .bashrc |- project (working dir) |- bin/ (or apps) |- etc/ |- lib/ |- opt/ |- tmp/ |

ROOT/ |- home/{username}/ |- Desktop/ |- Documents/ |- Downloads/ |- .local/ |- bin/ |- .ssh/ |- .bash_profile |- .bashrc |- .bash_history |- bin/ |- etc/ |- lib/ |- opt/ |- tmp/ |

ROOT/ |- /Users/{username}/ |-Applications/ |-Desktop/ |-Documents/ |-Downloads/ |-Library/ |- .bin/ |- .ssh/ |- .bash_profile |- .bashrc |- .bash_history |- bin/ |- etc/ |- Library/ |- opt/ |- tmp/ |

ROOT/ |- Desktop\ |- Documents\ |- Downloads\ |- C:\ |- Windows\ |- Program Files\ |- Users\{username}\ |- .bashrc |

2.1 What is the HOME folder used for?

A HOME directory is the core of the user space, where you can store all your files, especially configuration files should be placed there. The user assigned to a particular home directory has permission to create and delete files and directories. On multi-user systems, however, it is not allowed to view or modify another user’s data unless it is granted access privileges. To learn more about access permissions and also rights to read, write, and execute operations on files check out the tutorial.

As you can see in Table above, the $HOME folder contains several built-in subdirectories on machines intended for personal use, regardless of the operating system. That includes folders corresponding to the contents of the Desktop, Documents, and Downloads. Installed programs are available in Applications on macOS, this corresponds to C:\Program Files on Windows, and in general, it is the bin directory on Linux.

2.2 Is HOME a working directory?

On a private computer, subdirectories with projects and data are usually created directly in $HOME. However, on shared computing infrastructures such as HPC clusters, the amount of memory allocated to a user in HOME is limited (e.g., 5GB quota). Thus, recommendation says to keep only configuration files and important installations there. The project data, virtual environments and specific software are stored in another location, referred to as a working space. Usually this is another directory located directly in ROOT, for example /work or /project. There, subdirectories are created for individual research groups or collaborative projects, to which specific user groups have access. Such organization on the computing infrastructure allows to keep order and optimize the use of resources, for example, by reducing the redundancy of files on which several users work concurrently.

Note that on most HPC infrastructures, including HPC@ISU and SCINet, queuing jobs that

write outputs to the $HOME directory is prohibited!

Instead, use the path /work/{group}/{user} on ISU and /project/{group} or /90daysdata/ on SCINet clusters.

2.3 Good practices for HOME organization

Whether you’re working on a local machine or a remote shared infrastructure, keep your $HOME directory neatly organized.

To configure your $HOME to work efficiently on a computing cluster, take a look at the tutorial Home Directory Setup in the section 06. High-Performance Computing of this workbook. More specifically, follow the directions in the tutorial to properly configure your ~/.bashrc.

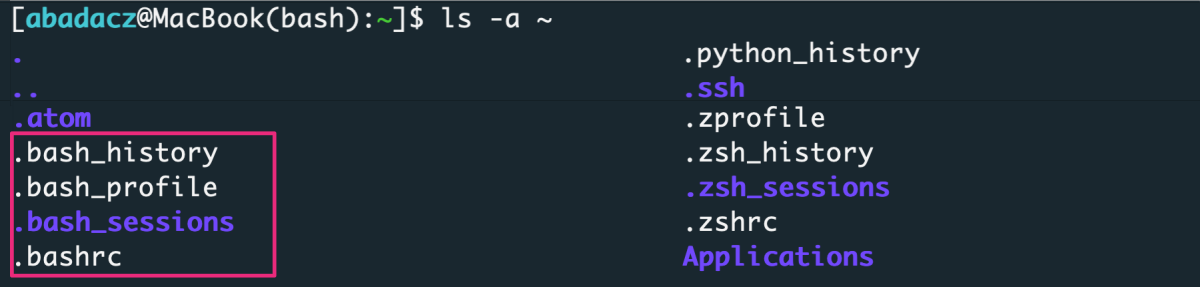

3. Unix Shell Configuration

Once you access the file system using terminal window or command prompt, the settings for the Unix shell will be stored in the .bashrc and/or .bash_profile files. As you noticed, those files are prefixed with a dot . what gives them a hidden property. That means they will NOT be listed in the result of ls command unless you use it with an -a flag, i.e., ls -a.

ls -a ~

Note that ~ refers to the $HOME of a given user.

Then, you should find .bashrc and .bash_profileon your screen.

To preview the content of these files type in the terminal window (from any location on the file system):

less ~/.bashrc

less ~/.bash_profile

To print the contents of a file on the screen use cat command:

cat ~/.bashrc

To edit a file in the terminal use text editor such as nano, vim or mcedit:

nano ~/.bashrc

3.1 .bashrc & .bash_profile

At first glance, the contents of these files may seem interchangeable. Whichever one you have, you can always ‘activate’ its updated contents with the source command:

source ~/.bashrc

# or

source ~/.bash_profile

By activate, I mean applaying to the current environment the changed values of the shell variables, loading new modules, adding new aliases to the list of known commands, etc.

So remember, changes made to .bashrc and .bash_profile files will NOT be visible in the Unix shell (e.g., newly added variable will be unrecognized) until you activate the changes with the source command. That will refresh the current shell environment.

So what really makes .bashrc different from .bash_profile?

Well, the ~/.bash_profile is loaded once, just after opening the terminal on the local machine or logging into the remote infrastructure. Whereas ~/.bashrc is read each time you start bash as an interactive shell (e.g., open new tab in the terminal). Thus, it is responsible for the default settings of your shell at the start. So, if you want to always have a certain prompt appearance or always load a bunch of modules at startup or be able to effortlessly call executable programs from a given path, specify these rules in .bashrc. Then, append the syntax provided below to your ~/.bash_profile. It will force the execution of ~/.bashrc in the scenario when ~/.bash_profile is called.

if [ -f ~/.bashrc ]; then

source ~/.bashrc

fi

To learn more about this topic, I recommend following the discussion thread on the superuser.com forum.

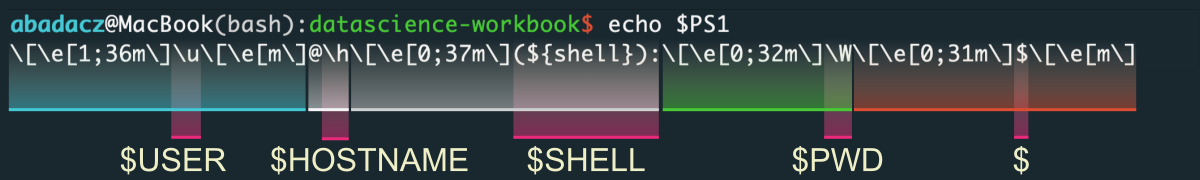

3.2 Setting up prompt

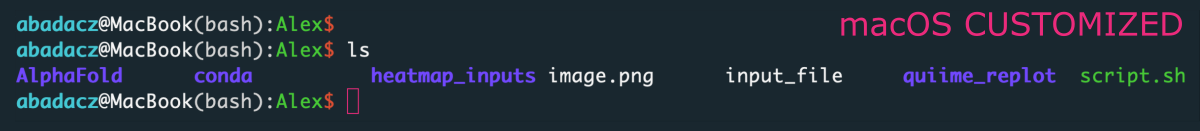

Prompt is a pre-defined field in the terminal emulator which tells you something about the current settings for the Unix shell. It always appears on the left-hand side of the command line in the terminal window. By default, the syntax includes who is the current user on which host and what is the current location in the file system. But this can vary on different operating systems. The default prompt is white, but everything can be customized to your needs, both the syntax elements and their colors. See the possible difference of customization in the image below.

The definition of a prompt is stored in the $PS1 variable. You can display its value just as any other shell variable.

echo $PS1

At first glance, the syntax may seem complicated. However, everything becomes easier when you break it down into the individual components. In the image, the colors highlight five chunks in the syntax. Each contains one variable, such as \u or \h (see the table below for a complete list of available options), and an additional code. If you look closely, this other code is repetitive and can be reduced to two unique syntaxes: \[\e[X;Ym\] and \[\e[m\] for start coloring and stop coloring, respectively. X denotes the text decoration, such as bold, dim, or underlined, and Y is a number coding specific color. You can find the exact definitions for available options below. Note that if you change one color to another, then stopping the color is not necessary. On the other hand, if you want to return to the default (white) color, you must use the syntax for stop. That is especially important at the end of the definition so that text typed on the command line will be in the default color (unless you wish otherwise).

The table below contains variables that can be used when defining a customized prompt.

| syntax | DEFINITION | syntax | DEFINITION |

|---|---|---|---|

\u |

current username | \d |

the date in format “Day-name Month day-number” |

\h |

hostname | \@ |

current time in 12-hour format |

\H |

full hostname | \j |

the current number of jobs managed in the shell |

\l |

terminal device name | \? |

exit status of the command |

\s |

basename of the shell | \! |

index of the command in history |

\v |

version of bash | \\ |

backslash |

\w |

working directory | \n |

new line |

\W |

base of working directory | \e |

an ASCII escape character |

\e[ |

start color syntax (non-printing characters) | ||

\e[m |

stop color syntax (non-printing characters) | ||

${var} |

use shell variable |

The table below contains the most popular text decorations and colors used to customize the Unix shell prompt. There are many more options that you can follow at misc.flogisoft.com.

| text decoration | foreground text color | prompt background color |

|---|---|---|

0 - normal text |

30 - black |

40 - black |

1 - bold text |

31 - red |

41 - red |

2 - dim text |

32 - green |

42 - green |

3 - italic |

33 - yellow |

43 - yellow |

4 - underlined text |

34 - blue |

44 - blue |

5 - blinking text |

35 - purple |

45 - purple |

7 - reverse text color with a background |

36 - cyan |

46 - cyan |

9 - |

37 - light-gray |

47 - light-gray |

You can test the result of your prompt style during development stage witch printf command (temporarily append a newline character \n to the end of your syntax when using printf). For a single element, you can use any pair of foreground text & background color, and a combination of multiple text decorations, all separated by ;. Note, however, that not all decorations (e.g., italic or blinking) work on all types of terminals.

# text decorations

printf "\e[1mBOLD\e[0m\n"

printf "\e[2mDIM\e[0m\n"

printf "\e[3mITALIC\e[0m\n"

printf "\e[4mUNDERLINE\e[0m\n"

printf "\e[5mBLINK\e[0m\n"

printf "\e[7mREVERSE\e[0m\n"

printf "\e[8mHIDDEN\e[0m\n"

printf "\e[9mSTRIKETHROUGH\e[0m\n"

# text colors

printf "\e[33mYELLOW\e[0m\n"

printf "\e[36mCYAN\e[0m\n"

# background colors

printf "\e[41mRED\e[0m\n"

printf "\e[45mPURPLE\e[0m\n"

# combined effects

printf "\e[4;31;43mUNDERLINE-RED-TEXT-ON-YELLOW-BACKGROUND\e[0m\n"

printf "\e[1;5;36;45mBOLD-BLINK-CYAN-TEXT-ON-PURPLE-BACKGROUND\e[0m\n"

^ Note that strikethrough option didn't work on my terminal. It should look like STRIKETHROUGH.

Set your colored Prompt syntax using variables and text decorations from the tables above and paste it into your ~/.bashrc following the given example, in which you will get the user@host:path$ for a root-user and user@host:path$ for any other user.

if [[ $USER = "root" ]]; then

PS1="\[\e[1;31m\]\u@\h:\w\$\e[0m "

else

PS1="\[\e[1;32m\]\u@\h:\w\$\e[0m "

fi

To get prompt like mine user@host(shell):path$ use the syntax below:

PS1="\[\e[1;36m\]\u\[\e[m\]@\h\[\e[0;37m\](\s):\[\e[0;32m\]\W\[\e[0;31m\]$\[\e[m\]"

3.3 Terminal Coloring

Prompt is not the only thing in the terminal that you can configure to your needs. Customization also applies to the background color in the terminal window, adjusting the styles of displayed file types, or highlighting a search expression in the results. Changing settings may work differently depending on the operating system or terminal type. Here, I will introduce settings that work on macOS and standard Linux (which also works on HPC).

Linux

In the previous section (customizing the command line prompt) the standard color codes for Bash and possible text decorations were introduced. Exactly same definition applies to setting styles for listing the file system when using the ls command. To avoid page scrolling let’s see these options again (find more at misc.flogisoft.com).

| text decoration | foreground text color | prompt background color |

|---|---|---|

0 - normal text |

30 - black |

40 - black |

1 - bold text |

31 - red |

41 - red |

2 - dim text |

32 - green |

42 - green |

3 - italic |

33 - yellow |

43 - yellow |

4 - underlined text |

34 - blue |

44 - blue |

5 - blinking text |

35 - purple |

45 - purple |

7 - reverse text color with a background |

36 - cyan |

46 - cyan |

9 - |

37 - light-gray |

47 - light-gray |

In Linux, the variable responsible for storing settings for coloring files and directories is called $LS_COLORS. It takes a string of elements separated by a colon : as a value. A given item consists of a file type with assigned styles using an equals sign, type=styles:. The names of a few types are predefined (see the list below), and the user can add as a type any format, such as *.png, where all files with PNG extension will have the assigned style applied. The styling is defined the same as for the prompt, i.e., any combination of numeric codes assigned to the colors and decorations of the text, all separated by a semicolon, e.g., di=2;36 for coloring directories in bold-cyan .

Important predefined types:

^ the complete list can be expolred at bigsoft.co.uk

di - directory |

fi - file |

ex - executable file |

ln - symbolic link |

|---|---|---|---|

pi - named pipe |

so - socket |

bd - block device |

cd - character device |

Thus, applying colors for listing the file system is as simple as copy-paste the following snippet into your ~/.bashrc file:

LS_COLORS='rs=0:di=1;34:ln=01;36:mh=00:pi=40;33:so=01;35:do=01;35:bd=40;33;01:cd=40;33;01:or=40;31;01:su=37;41:sg=30;43:ca=30;41:tw=30;42:ow=34;42:st=37;44:ex=01;32:*.tar=01;31:*.tgz=01;31:*.arc=01;31:*.arj=01;31:*.taz=01;31:*.lha=01;31:*.lz4=01;31:*.lzh=01;31:*.lzma=01;31:*.tlz=01;31:*.txz=01;31:*.tzo=01;31:*.t7z=01;31:*.zip=01;31:*.z=01;31:*.Z=01;31:*.dz=01;31:*.gz=01;31:*.lrz=01;31:*.lz=01;31:*.lzo=01;31:*.xz=01;31:*.bz2=01;31:*.bz=01;31:*.tbz=01;31:*.tbz2=01;31:*.tz=01;31:*.deb=01;31:*.rpm=01;31:*.jar=01;31:*.war=01;31:*.ear=01;31:*.sar=01;31:*.rar=01;31:*.alz=01;31:*.ace=01;31:*.zoo=01;31:*.cpio=01;31:*.7z=01;31:*.rz=01;31:*.cab=01;31:*.jpg=01;35:*.jpeg=01;35:*.gif=01;35:*.bmp=01;35:*.pbm=01;35:*.pgm=01;35:*.ppm=01;35:*.tga=01;35:*.xbm=01;35:*.xpm=01;35:*.tif=01;35:*.tiff=01;35:*.png=01;35:*.svg=01;35:*.svgz=01;35:*.mng=01;35:*.pcx=01;35:*.mov=01;35:*.mpg=01;35:*.mpeg=01;35:*.m2v=01;35:*.mkv=01;35:*.webm=01;35:*.ogm=01;35:*.mp4=01;35:*.m4v=01;35:*.mp4v=01;35:*.vob=01;35:*.qt=01;35:*.nuv=01;35:*.wmv=01;35:*.asf=01;35:*.rm=01;35:*.rmvb=01;35:*.flc=01;35:*.avi=01;35:*.fli=01;35:*.flv=01;35:*.gl=01;35:*.dl=01;35:*.xcf=01;35:*.xwd=01;35:*.yuv=01;35:*.cgm=01;35:*.emf=01;35:*.axv=01;35:*.anx=01;35:*.ogv=01;35:*.ogx=01;35:*.aac=00;36:*.au=00;36:*.flac=00;36:*.mid=00;36:*.midi=00;36:*.mka=00;36:*.mp3=00;36:*.mpc=00;36:*.ogg=00;36:*.ra=00;36:*.wav=00;36:*.axa=00;36:*.oga=00;36:*.spx=00;36:*.xspf=00;36:';

alias ls='ls --color=auto'

^ The alias line will apply auto-coloring when calling the default ls command.

^ More about aliases you can learn in the next section of this tutorial.

Do NOT forget to apply the changes to the current environment! Type on the command line:

source ~/.bashrc

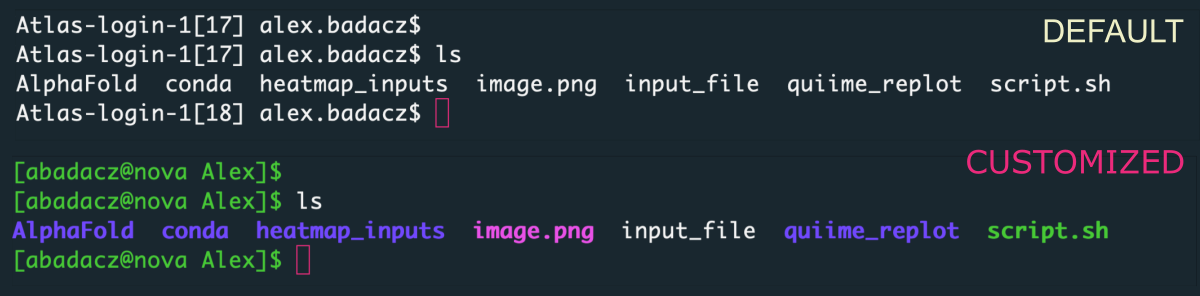

Let’s see the differences between a machine with default settings (top) and one with color customization for the user (bottom). The comfort of working in a customized terminal is much greater!

macOS

Linux configuration of terminal coloring may not have the desired effect on a macOS machine. In particular, the $LSCOLORS variable corresponds to the $LS_COLORS in the Linux variant. However, its definition is quite different. The syntax is a string of 22 letters combined in pairs to provide the styling for 11 predefined types of file system objects. The first character in a duo refers to the foreground text color and the second to the background color. Using capital letters will add bold decoration to the text.

The table below lists ordered objects with the default text and background (BG) colors.

| object | dir | symlink | socket | pipe | exe | block | char | exe-uid | exe-gid | dir-sticky | dir-other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| text | e | f | c | d | b | e | e | a | a | a | a |

| BG | x | x | x | x | x | g | d | b | g | c | d |

| ix | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

a - black

b - red

c - green

d - brown

e - blue

f - magenta

g - cyan

h - light-gray

x - default

^ capital letters add bold text decoration

Further, the $CLICOLOR variable forces using ANSI color sequences to distinguish file types. Also, make sure that selected terminal type for $TERM variable is an xterm-color. The setup is straightforward, simply copy-paste into your ~/.bashrc the snippet provided below:

TERM=xterm-color

CLICOLOR=1

LSCOLORS=Exgxcxdxcxegedabagacad

alias ls='ls -Gh'

3.4 Define aliases

In the Unix shell, alias is a text-like shortcut for the more complex set of commands that can be called directly from the command line by a user-customized name. Traditionally, aliases are defined in the ~/.bashrc file, so the predefined aliases are available for the user right after opening the terminal window. The syntax is straightforward, use the alias keyword followed by the quniue name to which you assign a value using an equals sign. The value is a string containing the stream of commands, with syntax identical to that used directly on the command line.

alias unique_name="command_1 | command 2 | command_3"

Adding aliases can be useful for:

- redefining the default bash commands to customized ones, as we did with the

lscommand, which when called without arguments actually uses those defined in an alias - simplifying frequently called commands with hard-to-remember arguments, for example, you can create an alias to log in to a remote machine and not bother to memorize the host’s name or IP

- maintaining a complex syntax of commands combined in a stream, for example, to routinely parse a certain type of text files from your analysis

- changing the development environment, such as switching the Conda distribution between Intel’s x86 and the M1’s ARM architecture on MacBook Pro

Keeping your .bashrc neatly organized will bring you convenience, especially when you want to change something after a long time. Therefore, it is suggested that you create a separate section in this file for all the ALIASES you will add over time. It is best to give this section a highly visible header. As a reminder, # is a comment character in the bash shell.

Below, you can find examples of some useful aliases that should be copy-paste into your ~/.bashrc file.

### USER's ALIASES ###

# redefine default flags for ls command

alias ls='ls --color=auto' # on Linux

alias ls='ls -Gh' # on MacOS

# simplify login process (replace $USER with your {username} on a remote machine)

alias login_nova='ssh $USER@nova.its.iastate.edu' # HPC@ISU

alias login_atlas='ssh $USER @atlas-login.hpc.msstate.edu' # SCINet Atlas

alias login_ceres='ssh $USER@ceres.scinet.usda.gov' # SCINet Ceres

# switch Conda distributions on your MacBook Pro

### (for details see tutorial in section 3 of the workbook: Setting Up Computing Mashine -> Installations on MacBook Pro)

alias source_condaX86="source /Users/$USER/Library/Miniforge3_x86/bin/activate"

alias source_conda="source /Users/$USER/Library/Miniforge3/bin/activate"

While the temptation is high, you must NOT create aliases to store passwords in this way. Doing so would be a serious threat not only to your privacy, but also a significant security risk to the entire HPC infrastructure and all users.

3.5 Load modules

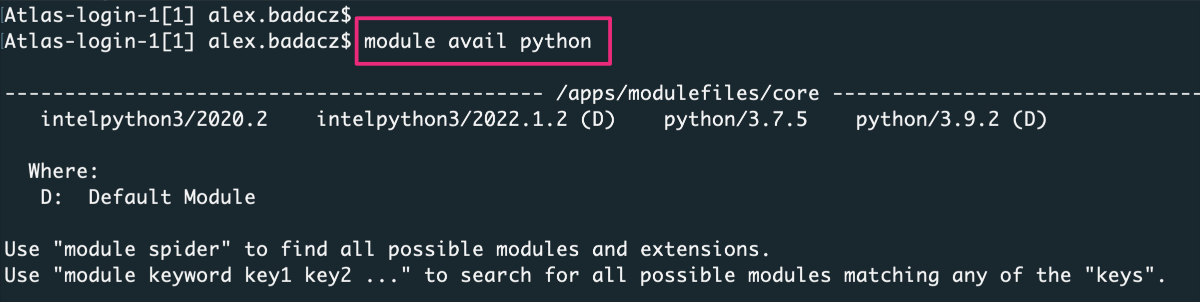

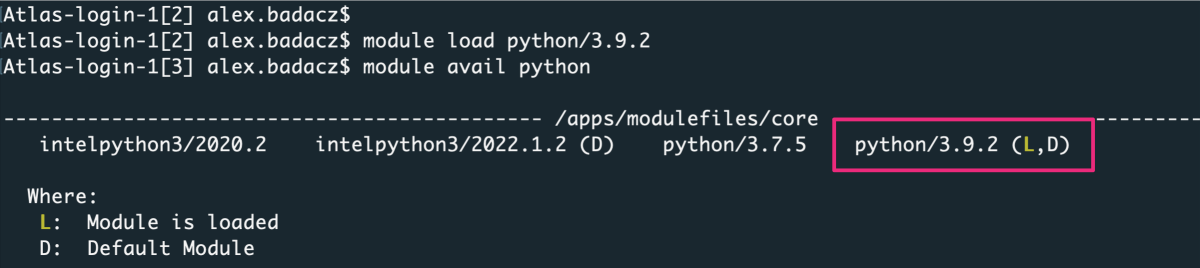

Module loading is more applicable to work on remote machines like computing clusters, where to avoid redundancy of software installed by each user individually, certain universal libraries are installed once from the admin level. Then each infrastructure user can load selected modules into their environment from among the available. Specifically, the user can select the versions of a given module that are appropriate for their analysis. To check the available variants of a particular module, use the module avail command then type the name of the library or software.

module avail python

The command returns a list of available variants along with the annotation (D) for the default suggested ones and (L) for the currently loaded ones (if applicable). To load or change a module variant use the module load command and the copy-paste the name of the library variant (select the name with mouse and then use the combination of keys CTRL+C and CTRL+V).

module load python/3.9.2

In case you want to always start your Bash shell session with a specific module loaded, the best solution is to add the command to your ~/.bashrc. This will simplify your working routine, especially if you have an entire list of necessary modules. So let’s say you would like to always have python/3.9.2 loaded by default into your environment. Thus, add the following snippet to your ~/.bashrc:

### USER's MODULES LOADED ON STARTUP ###

module load python/3.9.2

Prudence lies in moderation. So do NOT add modules used infrequently or only in a specific pipeline to your ~/.bashrc. Watch out for this, especially on a computing cluster, where the resources allocated for your $HOME are often severely limited.

So, how can you keep the organizations of the modules necessary for analyses?

The answer comes from virtual environments. You can create a new environment for a particular analysis and within it manage the list of necessary modules. For python-based environments, Conda will provide you with assistance. You can learn more by following the tutorial in section Setting Up Computing Machine: .

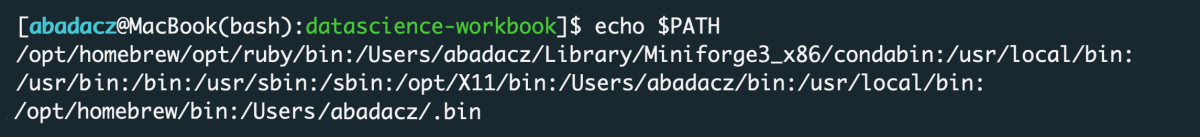

3.6 Export $PATH and more

Exporting a $PATH variable is probably the most commonly used example for the export command. It is also a common topic on programming forums, where novice bash users struggle with errors appearing when called programs don’t work. $PATH is an environmental variable that tells the shell where to search in file system for executable files called by a user. To see what file system locations are added to the list of paths searched to run an executable of a program, display the contents of the $PATH variable:

echo $PATH

The syntax of the $PATH variable consists of absolute paths to directories in the file system separated by a colon : (without spaces). The value of this variable is stored in the ~/.bashrc file. To add a new path, edit the ~/.bashrc file in any text editor (e.g., nano, vim, mcedit) and paste the new path after a colon. If this variable is not in your ~/.bashrc, you can copy the current value displayed with the echo $PATH command and paste it into the file following the example:

PATH="/usr/bin:/usr/local/bin:/bin:/sbin:/opt/X11/bin:"

You can also add a new path to the $PATH variable directly from the command line using the export command. Considering that your path of interest is a directory bin located in your $HOME directory (i.e., $HOME/bin), you can update the $PATH variable as follows:

export PATH="$HOME/bin:$PATH"

That means you just added a new location in the file system at the beginning of a previous state of the string being a value of the $PATH variable.

With the export command you can overwrite or update the value of any environment variable in the Unix shell. For example, directly from the command line you can change the number of commands saved in the Bash shell history:

export HISTSIZE=300